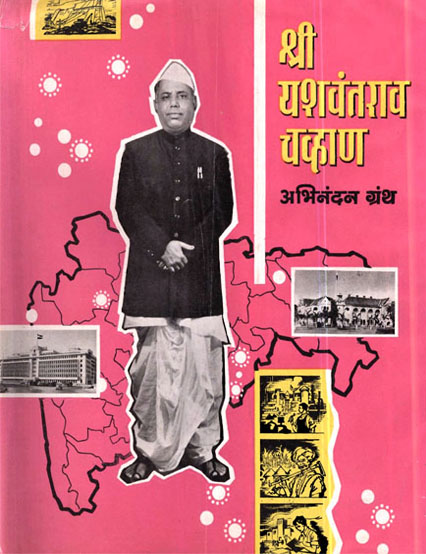

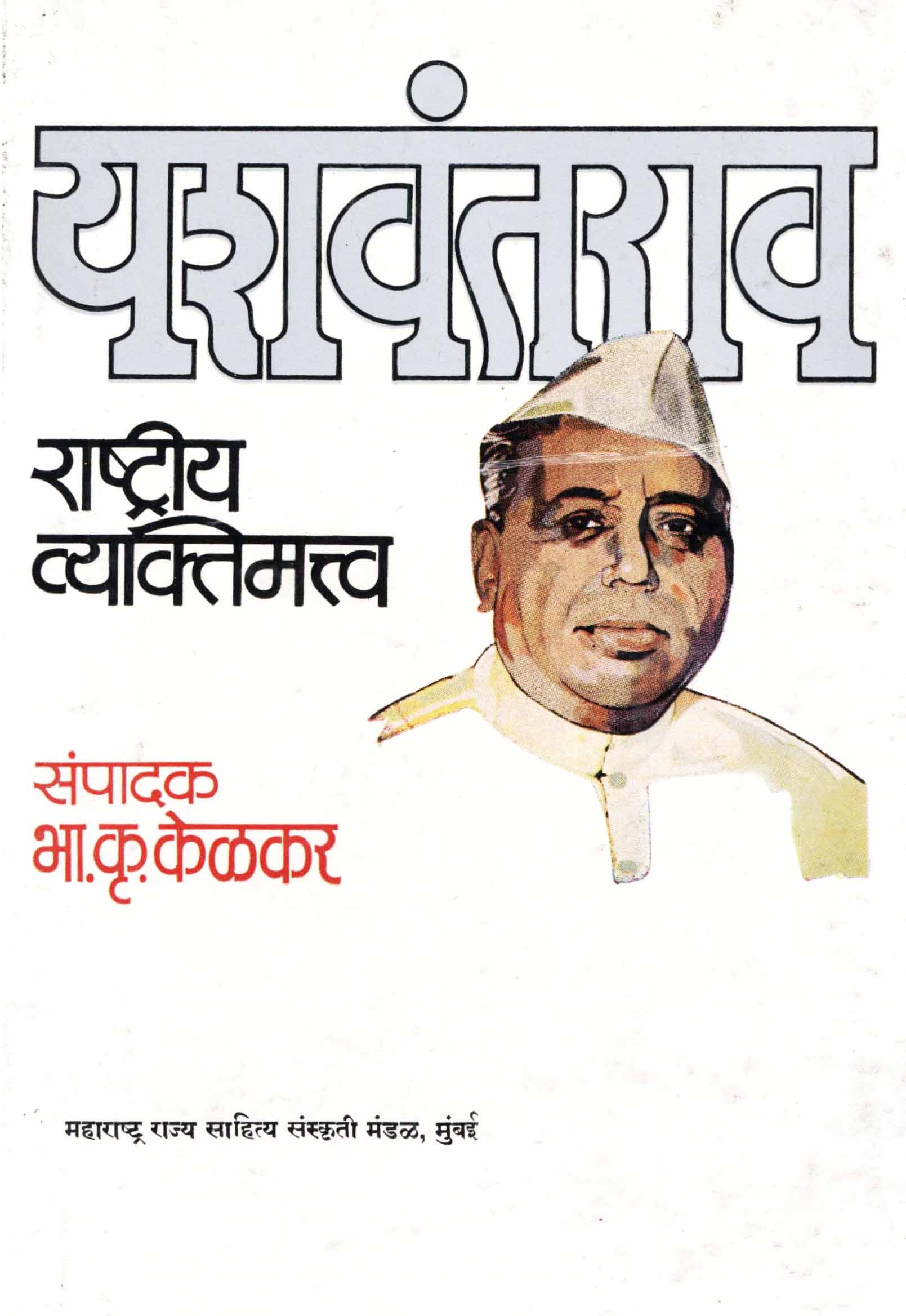

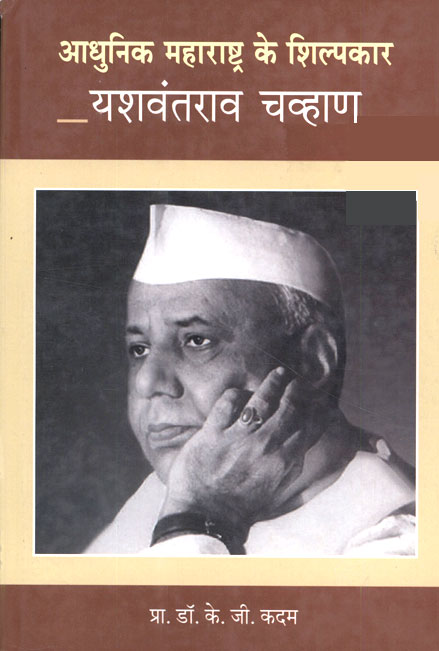

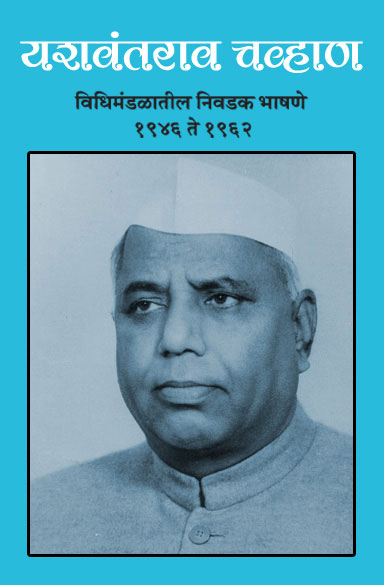

This outlook is demonstrated by the way he moves and behaves with people whether at his home, at their homes, in his office, or in large assemblies. There is something in his behaviour toward them, in the manner of his talk, his deportment, his approach, which makes it clear that he regards them as his peers in every way and is not comporting toward them from a height or a position of patronage. Tens of thousands of peasants and workers, and other folk from different walks of life, can testify from personal experience to this aspect of his personality of which they are the beneficiaries.

His understanding acceptance of the will of the people in Maharashtra in respect of its political setup provides an outstanding lesson in democracy. No doubt, he could have continued to maintain his position both in the organization and in the administration if he had desisted from taking the initiative in readjusting the setup of the composite Bombay State. Nobody would have blamed him. Yet he took the risk of being misunderstood, of losing caste with leaders and people alike, when it became clear to him that the people wanted a State in which all Marathi-speaking people would be together. His move in this regard showed great understanding, courage, selflessness —and faith in the ways of democracy, in the right of the people to live their own lives.

The same respect for and faith in democracy is reflected in his handling of the Opposition in the Legislature. He misses no opportunity of accepting the views of the Opposition whenever he is convinced that those views redound to the advantage of the people at large. For he realises that there are more roads than one to the people's welfare, that there are more ways than one to attain it, and that, where the interests of the people are concerned, no stone must be left unturned, no avenue left unexplored, even though such turning and exploration may be initiated by a member of the Opposition. The proceedings of the Legislature during the last few years provide ample and incontrovertible evidence to this effect.

The most charming and wonderful aspect of the democratic way as practised by Yeshwantrao Chavan is that he is so little self-conscious about it. He functions democratically not as a matter of policy or of expedience but because he cannot help functioning so. Democracy is in his blood, in the water and soil of the land that bore him, and so he exudes its various elements without let or hindrance. The democracy practised by him has been known to be extremely infectious; and many high and mighty personages-and others not so high and mighty but contemptuous of democracy nevertheless—have been known to take a leaf out of his democratic book because they found it irresistible.

Yeshwantrao Chavan is a true and great teacher of democracy not because he talks about it (indeed he talks very little of democracy or, for that matter, of anything else), but because he is putting it into practice all the time. Example is not merely better than precept—it's The Thing.