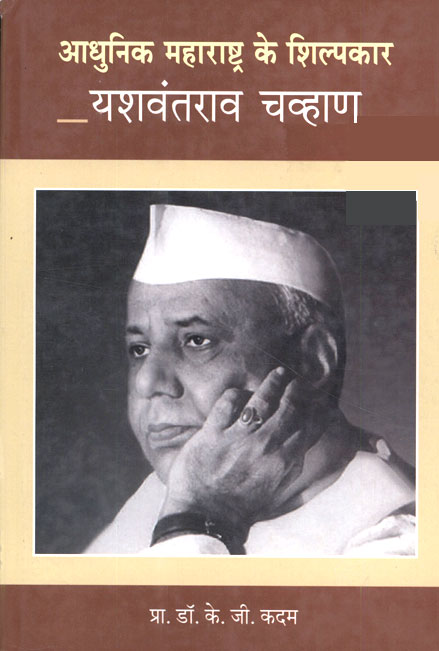

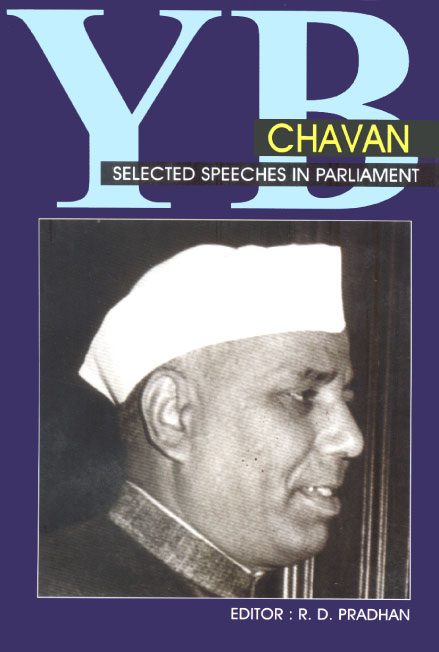

Emotions and passions were irrelevant and could only spoil the case; and at the same time the decision of Parliament, so long as it remained in force, had to be faithfully carried out. This was thus one of the major experiments of education in democracy which Chavan successfully carried on; and his deep and firm convictions supported by his intelligent understanding and sympathetic handling of the situation enabled him to do so. The bilingual Bombay State enjoyed the reputation of a well-administered State and arguments for and against it began getting gradually divorced from emotions and passions. This again was probably the most trying period in the career of Chavan when courage demanded control, reason prescribed restraint and understanding had to accept an approach full of conciliation.

But conciliation is one thing and reconciliation is another. Though passions cooled down, people were still not reconciled to the situation. They were still not prepared to accept the solution devised for them and anything that seemed to pacify the people provoked the politicians anxious to capitalise the situation. Conditions remained uncertain, and threats of 'struggle' lay always hanging in the atmosphere. No one could have foreseen the precise magnitude of the danger. Thus arose what may be called the second difficult test for Chavan. To rule might soon cease to mean to guide and to lead ; it might involve, on the other hand, the obligation to suppress and to shoot. Parliament no doubt is the symbol of Indian democracy but it still signified only an approximation of the basic human values, respect for which is the essence of democracy everywhere in the world. It seems to me to be highly superficial to say that as a clever politician, Chavan manceuvered to get on the occasion what he had wanted all along, viz., the creation of the State of Maharashtra. As a matter of fact, the situation confronted him in all its complexities and the issue for a man of convictions and values was extremely difficult. The decision of the Parliament was to be carried out and Chavan was prepared to persuade and to plead, to argue and to administer. But the decision itself could only be for the people, for their interests and well-being. If it therefore led to a point where it would be imperative to suppress and to shoot, Chavan would not defy but would stand down; he would not shoot. It was perhaps necessary for the Parliament to have second thoughts on the matter. The force of persuasion was thus turned in the other direction and the result was bifurcation. This steady movement, in the context of an explosive situation dominated by jingoism and chauvinistic passions, to the humanist core of democracy on which he maintained a fixed gaze all through the period constitutes the real basis of the hopes entertained of Chavan at present. He thereby set an example which effectively educated a whole segment of our population in democratic practice and provided a valuable lesson for others.